RACE & PLACE

Grief, a (grand)mother tongue

Love, loss, and the limits of language.

by MELE GIRMA

If grief is love with nowhere to go, I think it is also a language with no one to speak it.

After circling the sanctuary with a curl of incense trailing behind him for what feels like hours, the priest finally nods for us to sit. I sink into my seat in relief, exhausted. I cannot believe that I am here and that time is moving this slowly. It is the funeral for my favorite person in the world and I am bored, willing for it to be over.

My "Uncle" Yohannes rises to offer a few words in Amharic and I strain to understand. His voice is so familiar, the lilt and cadence warm and full of memories of summers at his home in South Carolina. As I listen I imagine I am a paleontologist, dusting away the dirt to reveal fragments of phrases I do understand: "Lemen silc atanesam," why don't you pick up the phone? "Lijochihen yibarik," blessing my children. "Ehwhalaeshet," future bounty. I let these words float together in my head and arrive at a memory of my grandmother I would like to sit with: she is beaming in her brown leather recliner, head tilted back with laughter as she picks up a call from a beloved. "Lemen tefach?" she sings, Where've you been?

Before our language was ever tongue, it was tangible.

This is a feeling I know well, the tender familiarity of hearing my people speak Amharic, tinged with the unease of not fully comprehending all of what they are saying.

Growing up among a tight-knit community of other Ethiopian diaspora in the Atlanta area, where most all the other kids my age could hold their own and then some in our parents' tongue, it always felt as though it meant something when I couldn't keep a full conversation without reaching out for English as a crutch.

This manifested in deep anxieties around language: perfectionism when writing, biting my tongue in class if I couldn't find the right way to articulate a thought, hesitating when strangers spoke to me in Amharic. But attempting to learn a new language means giving yourself over into misunderstanding for the sake of connection. Trusting in the listener to meet you there.

Relationships are a shared language developed between two people over time. My grandmother, who I only knew as Emaye, meaning mother, came to live with us when I was 8 years old. Back then her English was about as advanced as my Amharic, and so, before our language was ever tongue, it was tangible.

I still remember those early days when she first moved into our downstairs family room to recover following her back surgery in 2004. I remember the feel of the sticky green vitamin E gel the hospital sent her home with, how I'd help mom rub it into Emaye's healing scar, tracing my finger over the long indent along the valley of her soft back.

Once she healed up and began moving through our home as her own, no longer guest but full member of the household, I remember quietly studying the precision she possessed for every single task she'd complete: How she'd rip paper towels perfectly in half, claiming a full rectangle was too much. How she'd cut up mango with her favorite mint green knife from Back Home, the blade facing in toward her thumb without hesitation. How quickly every empty yogurt container in the house became Tupperware. I wanted to ask her why. How did she know the right way to do everything?

Eager to speak with her, I resolved to have us learn. For years each night before bed I'd go downstairs to her room with a different library book to try to help her practice her English—Madeline in Paris, Amelia Bedilia (which always made us laugh), and our favorite, Are You My Mother? (a phrase we grew to repeat to each other often). In return, she'd try to teach me Amharic, using a plastic white placemat of the alphabet.

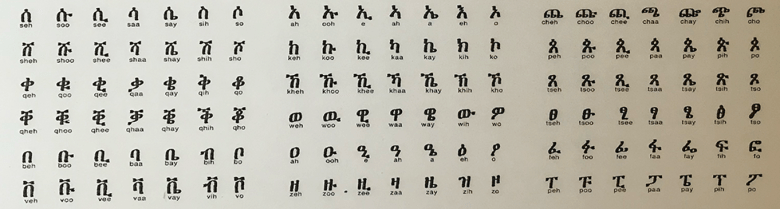

The Amharic alphabet is made up of hundreds of distinct syllabic characters following a pattern. Every character, a fidal, begins with a consonant, such as "h," and the successive characters in each seven-character line pair a vowel with the consonant, in this rhythm: ha, hu, hee, ha, hey, hih, ho. Emaye and I would chant like this nightly together over the placemat: la, lu, lee, la, ley, lih, lo. It never cemented into fluency, but there was meaning in the ritual.

Over time, Emaye and I developed a sort of half-language to speak comfortably with each other. Eventually we came to know enough of each other and our habits to infer meaning easily. It began with my haggled attempts at trying to discern the things she wanted, listing out the few Amharic words I knew with a loud question mark at the end. Or repeating English words in her accent, as though that'd somehow make it clearer. Where some relatives would hear my pitiful attempts at a sentence and laugh, she'd lean forward encouraging me—Gobez! Good job!—and ask me questions to clarify.

Though she had always been in my life, as a relative I saw on special occasions, a peripheral character in my early childhood, I was drawn to her here as the new addition to our family unit. Now, I can no longer remember our home without her there in my favorite room of the house, our hearth. She was the family member who had lived in Ethiopia the longest, the least tainted by America. My nearness to her meant a nearness to the culture I sometimes felt a stranger from.

In those early days with Emaye, I was earnest and verbose, fussy. I longed so deeply to win her over with language. Any time I said "I love you" to her, she'd simply nod and reply "Thank you, hode." But her love shone in the most practical of ways. If I took a nap on her red floral couch, I'd wake up with her gabi covering me. When I'd come home from school with my hair dry and unkempt, she'd whisk me down to sit criss-cross in front of her chair and pour jojoba oil onto my scalp, the cold surprise of the oil always jolting me upright a little. Then she'd massage it in slowly, miraculously turning the mess of my curls into two soft braids. And whenever the family would get a good box of mangoes from the Dekalb Farmers Market, she'd hide a few extra for us in her dinky downstairs fridge to cut up and eat together at night.

Emaye trained my palette to love what she loved: the tang of plain Greek yogurt with toasted flaxseed meal and a kick of mitmita, the magic of buna with a sprig of tenadam dropped in the bottom of the cup, subtly perfuming each sip. I was a 10-year-old kid with a fondness for Bluebell butter pecan and Häagen-Dazs coffee ice cream. To this day when I bake, I find myself cutting back the sugar in most recipes, hearing her voice in my head confidently remark that American sweets have bihzu siquar, too much sugar.

Today my Amharic is still riddled with grammar blunders, and her English only ever came to convey the essentials, but I was never too afraid of my own mistakes to fumble through speaking with Emaye, and she always made an effort to understand me. There was a forgiveness our conversations held, a security in knowing she'd listen past my mix-ups and misgendered verbs to hear the heart of what I was trying to say.

After she died, I felt a loneliness so deep, unlike anything I had felt before. It wasn't just that she was gone, but the safety I felt in her presence, to be my full self, without judgment, was gone too. She knew me to my core, she had studied me as I studied her. Who was I without her, knowing me? Without her understanding?

In the two years since her death, I often think about how I grew to know my Emaye so well, but there was still a part of her inaccessible to me—at times because of the language barrier, at times in spite of it. I did not know the source of her militant particularness or her deep empathy. What was it that moved her about the songs she cried to? What did she pray for each night? What life would she have chosen for herself if she did not dedicate it to her children?

To love someone and to try to know them is also to honor the limits of this knowing. There will always remain a part of them that is mystery to you. You can try for all of your living days and you will never quite get to the bottom of them. This is true with strangers. This is true with grandmothers. This is true with yourself. Sometimes I wonder if the things Emaye and I couldn't say in each other's native tongues helped us honor this mystery in one another.

By the time I reached my high school years, it was rare that Emaye and I couldn't piece together some semblance of understanding between us in our quick half-language, as much gesture and memory as it was Amharic/English hybrid. But on the occasions we couldn't, I'd call my mom (speed dial 2 of Emaye's old Motorola flip phone) and ask her to astergwami for us. My patient mother, a translator by trade, would listen to us each eagerly repeat ourselves, drawing out words for emphasis on either side of the speaker. Then once the missing word was found—my mother, our personal Vanna White revealing the hidden words between us—Emaye and I would look at each other and laugh with the newfound knowledge of what the other was trying to say.

For her part, it was typically the particulars of how she wanted a certain meal prepared or errand run; for mine, a description of the outings I'd be going on soon that she'd try to talk me out of. "But it's dark out," she'd reason. Or better, "It's almost dark out." "Betam regim menged," It's a long drive. "Lemen aldekemeshim?" Why aren't you tired? She was always finding an excuse for me to stay back home and sit with her as we each did our nothings. I was always quick to give in.

I don't know why she loved me so much. I don't know where it all went when she died. My love for her hasn't stopped, but I don't know what to do with it these days, where to put it. It's like having this deep sense of what I want to say, a word always on the tip of my tongue, but no ability to say it. No release.

I learned to love this woman. I know the precise shade of her coffee after just enough half-and-half. I know the gossip she'd laugh at and the Costco sweaters she'd hate and the moment to side-eye her during a drawn-out prayer.

Without her earthside, I am fluent in a dead language.

What does it mean, then, to communicate with Emaye now, as ancestor? Maybe there is another form of broken language we'll learn together, I don't know. But I know I feel closest to her in ritual. Incorporating, almost without thinking, her small habits into my daily life as a way of keeping her close.

Her habits have become instinct: The methodical way that I reheat my leftovers, running a day-old bagel quick beneath the faucet before toasting to revive it, or soaking my garlic cloves in a bowl of water first to make peeling the papery skin easier. My eye for ways to conserve and reuse—perfectly clean aluminum foil, ornate shipping boxes, the old yogurt container on my shelf storing steel cut oats. I think she'd be amused by her affect on me. Sometimes I imagine she is my houseguest.

Today I pull out her mint green knife, her bilawa, and unwrap a half loaf of banana bread I baked earlier in the week, still cold from the fridge. Her knife has sat untouched in my kitchen drawer these last two years for fear of dulling the blade, but today I am overcome with the sense that she'd be annoyed by this waste of a useful tool, so I lift it out of my rattling drawer.

We didn't always know each other. We learned each other. This is a grace not limited to native speakers.

I align the knife parallel atop the loaf and feel the give of the firm bread as the knife pushes through. I am communing with her, cutting her a slice. I think she will find it is not too sweet.

more from grief & other loves

Rest is Not Resistance, and That is OK

the night my Gramma died. I received a call around 11 p.m. the night my Gramma died. I immediately knew what the buzzing on my nightstand meant for my world from then on. That knowing prevented me from answering the phone. One, I wanted to hold onto my grandmother for one more night. Two, getting…

Holiday Season

When Christmas, Hanukkah, Ramadan, Kwanza and family gatherings of all kinds—the musical, cultural, food traditions—collide against a backdrop of losses, challenges, and major life shifts, the holidays can be a confusing time to welcome grief back home.

The World Since You Left

In this episode of Great Grief, Nnenna Freelon pleads with the moon, the sun, and the leaves about how to get in touch with her beloved Phil again. If grief isn't linear, then maybe sorrow is more than a season—perhaps it's a portal to the unknown.