One mild evening this past May, my partner and I ventured to a quaint bookstore in Atlanta's Virginia-Highland neighborhood for a Motherhood Beyond Bars children's book release party. The organization provides support for infants born to women incarcerated and works to reunify families. I was eager to attend the event and catch up with community comrades and their families in a chill, celebratory setting. We ran into Vanessa Garrett, a friend I'd lived with and co-facilitated career center classes with at the transitional center. As we talked, snacked on fruits and cheese, and played with Garrett's youngest daughter, it occurred to me that if Garrett hadn't been so persistent in seeking health care while we were inside—and been able to afford it—neither she or her daughter might be here today.

Free people might think that people in prison get free health care, but ask anyone who has done time in a state prison, especially in the South, and you might be surprised to find out just how much it costs to stay healthy.

Though medical copays vary, the typical cost to see a primary care physician in the United States is about $15 to $25. If the average federal minimum wage earner were to pay the same income-based rate as the average state prison worker, earning less than 70 cents an hour, they would shell out over $270 for a simple doctor visit, according to recent updates to a 2017 report by the Prison Policy Initiative, a nonpartisan organization that provides research exposing the harms of mass criminalization. That's the average among states that charge medical copays and pay incarcerated workers something. In North Carolina, that rate jumps to $720 for one doctor visit, and in West Virginia to over $1,090.

What's more disturbing is that many people in prisons across the South can't earn an income at all. This makes it impossible in states like Georgia and Texas to even calculate the comparable cost of seeking medical care. Though a few people, like Garrett, can afford the exorbitant costs, either because they have existing financial savings or supporters who can pay, many incur swelling medical debt that follows them for years.

Garrett is now the Reentry & Reunification Program Manager at Motherhood Beyond Bars. Like so many of us, she recalls her experiences putting in sick call forms and visiting "medical"—the hodgepodge system of health services within the Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) that receives all physical and mental health, dental (if even provided) and pharmaceutical concerns. Over and over again she submitted forms on the same issues while in custody without getting the care she needed.

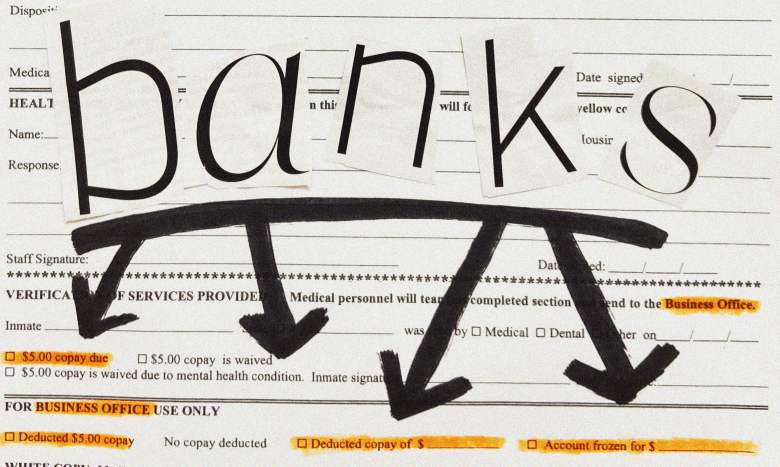

On top of that, every visit required a $5 copay for being seen, plus a copay for each medication. Ibuprofen was prescribed to everyone for everything, including colds and allergies (and later COVID-19 symptoms, even though the GDC rarely tested people). "They give [Ibuprofen] out like Skittles if you don't need it," Garrett recalled. "But if you do need it, it's not available." She said that, as a migraine sufferer, they would never give it to her if she complained of a headache.

Of all Garrett's negligent prison health care experiences, one issue had the potential to be life-threatening. After several visits for unusual numbness she was experiencing in both legs in 2017, Garrett developed a growth on the side of one leg. Some nurses said it was a bug bite: $5. Others told her to lose some weight, ignoring her characteristic numbness and the fact that she was falling down whenever her toes would go to sleep because she simply could not walk. Another $5.

"They were telling me I was just making it up, that it was in my head," said Garrett. "But when they finally did the ultrasound, they found out it was a blood clot that had broken itself down."

Garrett had deep vein thrombosis (DVT), a serious condition in which blood clots form in deep veins, usually in the legs. If untreated, clots can break loose and become lodged in the lungs, causing pulmonary embolism. "I had a cousin who died of an aneurysm," said Garrett, who began to think, "What, really, could my outcome have been?"

It took Garrett a year to get the diagnosis, the ultrasound being scheduled only after she secretly expressed concern to a nurse she felt close to who recognized the telltale signs of DVT. To Garrett, there's no doubt this was financial exploitation that could have cost her her life. "I was paying for them to not treat me, to not take me seriously," Garrett explained.

Garrett calculated the total amount wasted on the matter to be $100 or more, which might not sound like a lot until you remember that in prison, most paid workers earn less than a dollar per hour, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. For perspective, Virginia offers the highest paid prison minimum wage in the South at $0.27 an hour. Garrett made nothing.

The fees keep adding up

On top of taxes and social security, almost all workers in prison incur deductions that free workers do not. These can include things like fines, court costs, user fees, mandated savings deductions and state-specific ad hoc funds which have no relation to those paying for them.

For instance, in state-run facilities in Georgia, incarcerated workers' earnings are involuntarily deducted for a Crime Victims Emergency Fund, even if the employee is serving time for a victimless offense. This fund was created by a statute in 2014, and is currently administered by the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, the same agency responsible for distributing federal Victims of Crime Act (VOCA) grants in Georgia. VOCA similarly appropriates its funds from workers convicted of federal crimes. These fees are taken out on top of federal and state taxes. That's right—people incarcerated pay taxes, too, contradicting the misleading language on the Office for Victims of Crime website, which states they don't take money "from taxpayers." The IRS assures us incarceration doesn't exempt anyone from paying taxes.

Another Georgia deduction is for "room and board," initially implemented as a way for the state to automatically scoop rent from the paychecks of those participating in work-release programs in Georgia transitional centers, the only instances in which a person in GDC custody can earn a quasi-normal paycheck. That's despite the state's receipt of per-person federal subsidies to house everyone, which is why this particular deduction has had me scratching my head for years.

Ultimately, these whopping deductions put people in a bind and, when unaffordable copays are factored into the equation, it's no wonder that so many individuals in state prisons choose not to go to the doctor at all.

Georgia isn't the only state where the rising cost of inadequate medical care is being passed along to those suffering because of it. As of August 2019, only 10 states—none of which are in the South—are alleviating the prison health care crisis by not charging copays. People in most state facilities face unsettling income-to-copay rates, and many people in state prisons across the South never have the opportunity to earn an income at all.

Seven states in the nation—all in the South—follow slavery clauses in their respective constitutions and force those they incarcerate to work without pay, but nonetheless still charge medical fees: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas. And state leaders think this is fair.

"If we want to be fair that's fine," said Jennifer Toon, Mental Health Peer Policy Fellow at the Coalition for Texans with Disabilities. "Then pay me for my labor and we'll do it like everyone else in the world."

The reason behind rising copay costs in the South

Toon herself has nearly two decades of personal experience navigating the Texas Department of Criminal Justice's (TDCJ) medical copay system, which has changed drastically over time. In 2011, Texas passed HB26, requiring incarcerated folks to pay a whopping $100 per year for medical care, whether they saw a doctor once or many times. Before that, Texans in prison paid $3 per visit and, since 2019, they pay $13.55 per visit, a rate still higher than any other state, according to PPI data.

State Representative Jerry Madden (R-Plano) carried the $100 copay bill in Texas, and made failed attempts at doubling it to $200 a few years after the law went into effect. Madden and other proponents of steep health care copays have argued that they offset state costs by generating revenue. Yet, the $100 Texas copay not only brought in less money for the TDCJ, it also created a medical crisis.

"When they passed that $100 copay, we saw the ambulance all the time," Toon said. "People were falling out from kidney failure and cysts and things that could've been caught."

It's no secret that prison profiteers want to deter those incarcerated from going to the doctor.

Alabama's copay policy makes it clear that copayments for health services are used to force people to "make resource allocation decisions," a cruel way of making folks choose between medical care and food, clothing, hygiene items, and other necessities.

Georgia's policy uses the term "self-initiated visits" to make it seem as if seeking medical attention is a leisure activity, or even a choice, rather than a basic need. Even though studies show these strategies are intended to limit access to health care, presumably to reduce costs, a survey from the National Institute of Corrections found that none of the cost-saving initiatives implemented in the Federal Bureau of Prisons had a significant impact on per capita health care costs and, in certain cases, resulted in higher costs.

This outcome may in part result from the overall policies of "cost control" states, which tend to incarcerate more people per capita and dish out longer sentences, while their parole boards aren't held accountable for deviating from their own policies and statutory directives for releasing people. It's a combination of factors that contributes to a rapidly aging prison population. The high-cost burden to individuals just leads to compounded medical problems for a portion of society that is statistically sicker than most.

If it were really about saving taxpayer dollars, Southern states like Georgia, Texas, and Alabama could devote more of their budgets to preventive care or at least placing competent medical professionals in their facilities. Preventing even a small portion of the unnecessary, catastrophic issues which arise from sheer negligence and years of unmet health care needs seems like a no-brainer way to lessen the cost burden.

What happens in the case of chronic care?

One has to wonder how much Southern states benefit financially from pay-per-visit copays, particularly when it comes to chronic care. The GDC, TDCJ, and other state prison businesses draw a distinction between unplanned needs, like colds and injuries, and care for chronic conditions, which aren't subject to charges or ongoing fees. Chronic care is generally defined as routinely scheduled visits between a patient and a health care provider for a recurring medical condition, like blood pressure issues or diabetes. People in prison want these conditions to be classified as chronic care—as state regulations say they should be—because then they won't have to pay for weekly or monthly visits and corresponding medications.

In Texas, everyone is screened for chronic illnesses at free annual visits. To work around exorbitant medical costs, Toon said, "If you developed symptoms between the annual visits, [you] just wouldn't go up there [to medical]." Toon and others also learned to word their sick call requests in such a way that made the symptom likely to fall under a medication they were already taking for a chronic condition, if they were so lucky. Otherwise, she said, "They avoided medical like the plague."

Georgia is a little different. Our state policy allows for the screening of potential chronic illnesses during the prison intake process and upon transfer. The problem is that people often spend years, sometimes decades, at one prison. This makes it far less likely that basic conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure will be discovered and properly managed, even though terroristic living conditions and a lack of access to nutritional food contribute to the increased frequency and earlier onset of these diseases among those incarcerated when compared with freeworld populations.

The lack of free health screenings in both states are surely to blame for a number of horrific outcomes for people, including those who end up dying of cancer while incarcerated or shortly after being released because the disease was not discovered until it was fatal.

"There's a documented history of my sciatica problem going back to 2014," Amanda Chaney told me. "But when I asked about being on chronic care for it at Arrendale [State Prison in Georgia], they told me it wasn't covered." Chaney is a 36-year-old friend of mine; we lived in dorms and worked together at two GDC facilities over the course of many years. For her excruciating back problem, Chaney would go as long as she could and, finally unable to bear the pain, she'd put in a sick call only to be prescribed five days' worth of medication.

The GDC policy lists certain illnesses as requiring chronic care, including diabetes, hypertension, thyroid disease, HIV and cancer. These things are monitored through routinely scheduled follow-ups that do not require copays. "Chronic pain" is also included but, as Chaney's story illustrates, it seems to be arbitrary whether or not—and when—a condition is classified as chronic.

According to Garrett and Chaney, GDC medical staff seem to be creating a situation in which people have to submit sick calls and pay copays repeatedly as a means of dealing with untreated, ongoing conditions. Chaney said at each visit, nurses advised her to put in another sick call if she was still having issues. This cycle of literally paying for a lack of treatment continued for years, until Chaney's recent release finally afforded her the opportunity to see a legitimate doctor—eight years after the onset of her painful condition.

In Texas, according to Toon, the main problem is less about prisons creating situations where more people would have to return to medical over and over, and more about the quality of care, which is simply lacking. "The medical at the unit level was consistently ineffective, cruel, and they had the attitude that, whatever it is, you're making it up… as if you don't know your own body," Toon said.

A chilling example of medical staff skepticism turned deadly in April of 2018 when Melissa Burgeson, also incarcerated at Arrendale in Georgia, died during emergency surgery for complications from pneumonia. Following Burgeson's death, the Arrendale warden, Brooks Benton, posted a message on her memorial webpage in which he noted, "Miss Burgeson was a hard worker who believed in helping people and completing the job. She was not a complainer or disrupter."

Benton's words were true to fact. In the 25 years of warehouse, maintenance, and prison industries labor that Burgeson provided, she only filed two grievances and requested to see medical a handful of times, one of those being the day her finger was cut off while working in the garment factory. Though GDC employees are eligible for retirement after 25 years of service, the state never compensated Burgeson a penny for the work she provided.

Her friends recall that she was reluctant to put in sick calls because of the lack of actual care received for the unaffordable copays, but eventually Burgeson did seek medical attention when her symptoms worsened. Suffering from pneumonia, the prison's medical staff refused to see Burgeson several times in the days leading up to her death. They instead insisted that she take Tylenol and drink lots of water.

Though more and more people are wising up to the problem, the myth that those in prison with health care needs are being treated for free—or at all—still dictates the opinions of the majority. Burgeson's death is a tragedy that makes clear what's really happening in our prisons is a state-made crisis, not entirely different from the health care crisis in our greater population but more distressing, more dire. The crisis isn't only one of cost, but care—a grave illustration of how we treat and think about people in prison overall. We're so eager to treat people in prison cruelly that we are willing to pay more money to do it. All across the South, inside prisons and beyond them, we're letting people suffer treatable conditions, die of curable illnesses.

more in pop justice:

'It's not a story—it's a life:' A look at Snapped, from the inside

Come on Barbie, give us nothing!

Sources:

- Alabama Department of Corrections: Inmate co-payment for health services

- Brennan Center for Justice: The federal funding that fuels mass incarceration

- Employees' Retirement System of Georgia: Employees' Retirement System of Georgia

- Georgia Department of Corrections: Charges to offender accounts for health care provided

- Georgia Department of Corrections: Chronic Care SOP

- Rules and Regulations of the State of Georgia: Board of Corrections, Medical Services

- HealthCare.gov: Health coverage for incarcerated people

- Internal Revenue Service: Reentry myth buster

- Interrogating Justice: A look at the United States' aging prison population problem

- Lamb-Mechanick & Nelson: Prison health care survey: An analysis of factors influencing per capita costs (p. 11)

- Memorial Park Funeral Homes & Cemeteries: Miss Melissa Burgeson, 47

- National Commission on Correctional Health Care: Charging inmates a fee for health care services

- Office for Victims of Crime: Crime Victims Fund

- Pew: Prison Health Care: Costs and Quality (p. 9)

- Prison Legal News: Texas: $100 medical copay for prisoners generates less revenue than expected

- Prison Policy Initiative: How much do incarcerated people earn in each state?

- Prison Policy Initiative: The steep cost of medical co-pays in prison puts health at risk

- Prison Policy Initiative: Momentum is building to end medical co-pays in prisons and jails

- The Texas Tribune: Some inmates forego health care to avoid fees

- The Texas Tribune: Texas House, Senate budget plans tens of millions apart on prison health care

- Vera Institute: Aging out: Using compassionate release to address the growth of aging and infirm prison populations